“It was a day in our near future…”

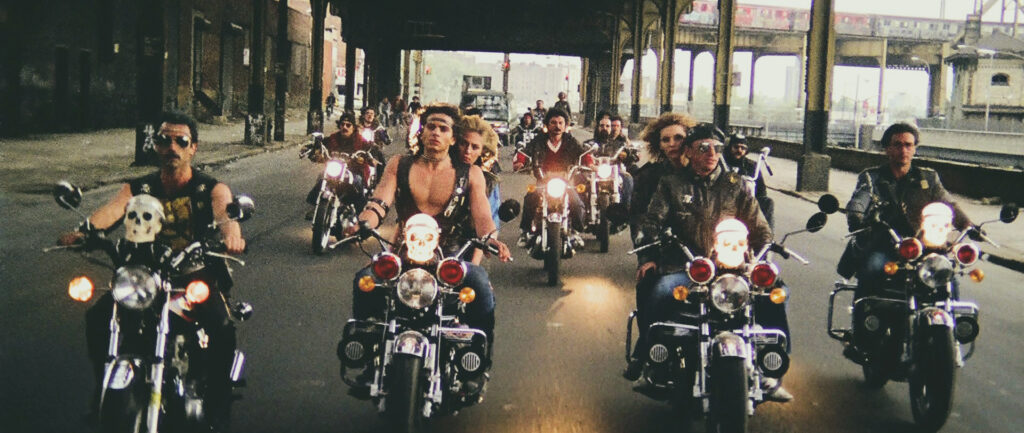

Hands of Steel, 1986

I’m broadcasting live from one of those moody altered states of consciousness we love to navigate, sailing between dreamlike mindscapes and ghastly worst-case scenarios as we search for the meaning of reality. We often hear that what we call reality is revealing itself to be as gruesome and bleak as our dystopian literature and movies imagined it to be, and that’s one reason why so many of us go back to them for comfort and guidance. I make no exception, as most of the movies I gravitated towards during the past months lie well within the deep and vast territory of fictional eschatology.

Half hidden behind the well-deserved glory of films considered of greater cultural value, of which they recreate the themes, the atmospheres and the aesthetic, lies the particular sub-genre I’ve been obsessing over lately: the Italian wave of post-atomic b-movies from the early 1980s directed by the masters of genre cinema such as Lucio Fulci, Enzo G. Castellari, Sergio Martino and Joe D’Amato – films mostly commissioned to them to capitalize on the international success of Mad Max, Escape From New York and The Warriors.

A Sucker For B-Movies

I admit to being a sucker for B, C and even some Z movies since I was a teenager. I remember some blissful Saturday afternoons of late summer and early fall, in the first lazy weeks of school, riding the scooter to meet my friends at the video store and renting as many movies as we could possibly binge-watch in a weekend. Obviously, we were never too much into open-air activities; we spent most of our time in dusty basements and rehearsal spaces blasting with music, wrapped in a thick cloud of smoke – the ideal nurturing ground forever faithful b-movie aficionados.

With my adolescence set in the ‘glory’ days of Napster and dial-up internet access, the only b-movies I could access at the time were those included my dad’s selection of Roger Corman’s timeless classics, like The Man With The X-Ray Eyes or his legendary Poe cycle with Vincent Price, alongside some late night-TV staples such as Fulci’s L’Aldilà or Ciccio Ingrassia’s The Exorcist: Italian Style. Then one evening, on the way home from the library, I entered what is probably the smallest video rental store I’ve seen to this day. It was maybe lacking on some of the classics that could have made it more frequented, but the manager knew his Ted V. Mikels and his Russ Meyer and had stocked up on all sorts of b-movie treasures. I unexpectedly and suddenly got access to all of the stuff I’d only seen mentioned before in short but enthusiastic blurbs on the heavy metal magazines I read after school. Movies coming from the darkest, goofiest blind corners of the human mind; failed or half-successful, yet always brave, attempts to recreate our wildest dreams and nightmares. The excitement and wonder I felt when a film managed to truly work its magic despite – or actually even thanks to – the low-budget and DIY approach made me understand why some of my favorite bands had chosen to dedicate some of their best songs, if not their entire artistic output, to singing their love for b-movies, especially of the science fiction horror kind.

Some of those movies turned out to be way less exciting than their bombastic titles had led me to believe, but on other wonderful occasions, they managed to live up to the outlandish names and alluring trailers that accompanied them. That magic often happened when visionary creators turned the camp control knob up to eleven without any shame or second thoughts, or when they managed to “mix exploitation film with art film… and make money” as John Waters said of Roger Corman before introducing him as one of his all-time heroes at the Provincetown Film Festival in 2012. That’s a lesson many directors learned from the “B-Movie King” himself, from his well-known apprentices like Francis Ford Coppola to his overseas admirers like Antonio Margheriti and the other prolific genre-shifting directors responsible for some of my favorite movies in the kingdom of b-cinema.

Apocalypse Italian Style

I had a lucky chance to talk about this with Claudio Simonetti of Goblin, the man behind some of the most memorable soundtracks in the genre, thanks to my friend Andrea who passed him over to me on the phone. When I asked which of his compositions would be best fitting as a soundtrack to our own apocalyptic times, Claudio said he’d choose the theme he wrote with Goblin for George Romero’s Dawn Of The Dead but agreed the one he made for Sergio Martino’s Hands of Steel would fit as well. I asked him specifically about the latter because it’s been one of my favourite movies to watch during the past few months. He said working on the soundtrack for Castellari’s The New Barbarians and Martino’s Hand of Steel brought him to explore atmospheres and places in music he wouldn’t have gone otherwise. Since he always works on the finished movie, Sergio Martino’s dark vision of the future for Hands of Steel influenced him greatly in his work on the soundtrack. The movie now seems prescient of our present and future, “because the worst is yet to come,” Claudio concluded.

If b-movies, in general, are somehow a fitting metaphor for life – with their poorly acted scenes and clumsy non-sequiturs, alongside flashes of over-the-top genius and glory – then post-apocalyptic b-movies are well suited to the moods and fears of our times, as they portray life in the aftermath of a man-made disaster caused by greediness and fear and fueled by racism and violence. Its Italian “post-atomic” division was part of a huge international trend launched by Miller and Carpenter and fueled by plenty of American, French, Japanese and even Filipino productions, but the Italians brought us some of the most colourful and interesting portrayals of the future of our species.

In fact, only some of the Italian so-called ‘post-atomic’ movies are actually set in the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust: in the last years of the Cold War, nuclear warfare didn’t seem anymore to be the only possible worst-case scenario for mankind. The 1980s were also “the decade we almost stopped climate change” according to The New York Times. Sergio Martino’s 1986 film Hands Of Steel argued that, if big corporations could have created an invincible cyborg able to kill scientists who threatened to warn the authorities about the alarming levels of pollution caused by their business, they definitely would have – but they didn’t need to, because those scientists worked for them,as we now know. Lucio Fulci chose to wager on the concept of eternal recurrence with his Warriors Of The Year 2072, portraying a new authoritarian age in Rome where violent TV programs are used to pacify and distract the population from the harsh living conditions they endure. Gladiators on motorbikes evocative of Romero’s Knightriders ride in formation along Ponte Sant’Angelo in Rome, speeding towards their televised death match in one of the most visually compelling representations of mankind’s race towards its own destruction.

Enzo G. Castellari, known outside of Italy mostly for being one of Quentin Tarantino’s favourite directors, contributed generously and gloriously to the genre with no less than three movies. Taking the themes of Mad Max and The Warriors a few steps further into “bikexploitation” territory with 1990:The Bronx Warriors and The New Barbarians, he ultimately put humanity’s future in the hands of rebel biker gangs sometimes looking like the Hell’s Angels – because they are – other times more like cyberpunk templars of the future. The last and best of his triptych, Escape From The Bronx (1983) envisions the bleakest future developments of wild, unregulated gentrification in New York: a ruthless corporation employs a battalion of “Disinfestors” to push the remaining inhabitants out of the Bronx by any means necessary, fire and gas included, in order to tear it down and rebuild it into an expensive new “city of the future.” The movie follows biker hero Trash – previously seen leading a gang of bikers played by the New York chapter of the Hell’s Angels in 1990:The Bronx Warriors – as he joins a motley crew made of mercenaries, reporters and surviving Bronx gang members who plan to kidnap the president of the evil General Construction corporation.

The contribution of the “Italian Roger Cormans” to our futurama of post-apocalyptic scenarios is made all the more colourful by their previous experiences in a wide variety of film genres – from peplum to western, giallo, horror and gore. Castellari and Martino were strong in exploring the fascination with cynicist trigger-happy villains in a lawless no man’s land, which their post-atomic wastelands shared with the old West; Joe D’Amato added a gory touch to his 1983 movie Endgame by lingering on the gruesome details of a society rapidly sliding into uncontrolled violence and survival of the cruellest. Lucio Fulci, coming from a string of successful horror movies that elevated him to cult legend, nailed the atmospheres of his Warriors of the Year 2072 by referencing Corman’s Pit and the Pendulum in his Alphaville plot twist, depicting Rome as a glacial plexiglass-covered megalopolis dominated by an artificial intelligence bent on controlling mankind through virtual-reality experiences of medieval torture.

There Is No Future – The Future Is Now

If we slide fifty years back in time through the wormhole opened by their beautifully ominous synth-fueled soundtracks, the elaborate medley of imagined universes brought to us by these movies can work its way through the haze of our own visions of future horror, merging them in a kaleidoscope of shared representations of apocalyptic scenarios. They’re the perfect companion for hazy, foggy, reflective late nights spent contemplating our vain illusions of control, our increasingly grim prospects and the mindless late-capitalist routines we perform, leaving us unable to swim against the insanity of it all.

Part of what makes post-apocalyptic movies feel so realistic is that they never show mankind having learned a lesson from their past ever. In most of them, the fall of our civilization is self-inflicted, and a return to the state of nature is inevitable because that’s exactly what most of us expect to happen. However, the ultimate purpose of movies, as Claudio Simonetti put it, is to enable us to explore places and atmospheres we wouldn’t be able to access otherwise. In the case of post-apocalyptic movies, they are also, on some level beyond pure enjoyment, an attempt to warn us about the consequences of our inaction. There may be few chances left for mankind to rise significantly above the good old homo homini lupus motto before our time is over, but that’s no reason to stop striving to get there – be it through science, art, education, civil disobedience, or simply by practising the most rewarding yet elusive of skills: the ability to truly open our minds to other perspectives.

—–

¹ https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-return-of-the-b-movie-king-1440020333

² Claudio Simonetti was presenting a new edition of Goblin successes in vinyl reissue at the 2020 edition of MEI in Faenza. You can listen to the whole interview (in Italian) on my SoundCloud page at https://soundcloud.com/calderollins/claudio-simonetti

³ Available on Discogs: https://www.discogs.com/Claudio-Simonetti-Vendetta-Dal-Futuro-Morirai-A-Mezzanotte-Conquest/master/1532429

⁴ “Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change”, by By Nathaniel Rich, The New York Times, August 1, 2018, available online at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/08/01/magazine/climate-change-losing-earth.html

⁵“Shell and Exxon’s secret 1980s climate change warnings – Newly found documents from the 1980s show that fossil fuel companies privately predicted the global damage that would be caused by their products” by Benjamin Franta, The Guardian, September 19, 2018, available online at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2018/sep/19/shell-and-exxons-secret-1980s-climate-change-warnings

—–

Italian Post-Atomic Movies

- 1990: The Bronx Warriors, Enzo G. Castellari, 1982

- Warriors of the Year 2072 (The New Gladiators), Lucio Fulci, 1982

- The New Barbarians (Warriors of the Wasteland), Enzo G. Castellari, 1983

- Escape From the Bronx (Escape 2000), Enzo G. Castellari, 1983

- 2019, After The Fall of New York, Sergio Martino (Martin Dolman), 1983

- Yor, the Hunter From the Future, Antonio Margheriti (Anthony M. Dawson), 1983

- Endgame, Joe D’Amato, 1983

- Atlantis Interceptors, Ruggero Deodato, 1983

- 2020 Texas Gladiators, Joe D’Amato, 1984

- Hands of Steel, Sergio Martino, 1986